June 17, 2020

This is a story about a tragic loss of fourteen airmen on a routine cargo run in the black of night over South Vietnam; an on-going mystery

about the actual cause of their deaths after years of searching for the answers; and the essential details that have emerged about the circumstances following the discovery and disclosure in mid-2019 of a long closely-held Air Force accident investigation report. It is also the sad story of how their loved ones were successively misinformed at the time of their loss about recovery of their remains, and then never told of the investigation findings up until this day, the 54th anniversary of their deaths. Finally, it reveals how the military's personnel information about each of the lost airman, as publicly disclosed on the Vietnam Memorial websites, to this day has misstated their cause of death and failed to show their Purple Heart awards. What follows are the known facts in honor of their sacrifice and memory.

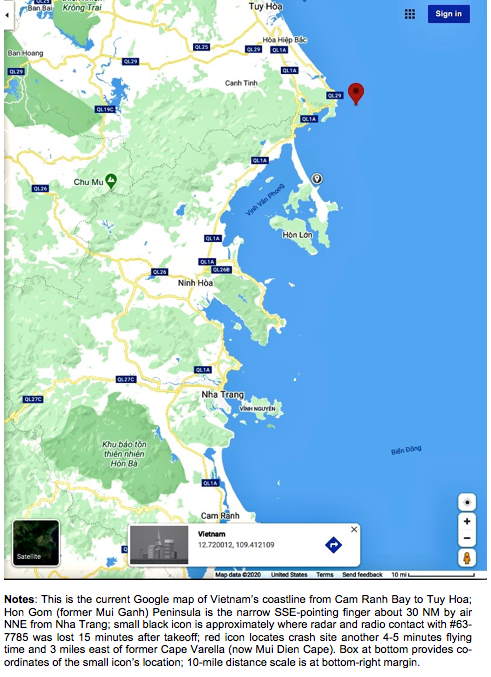

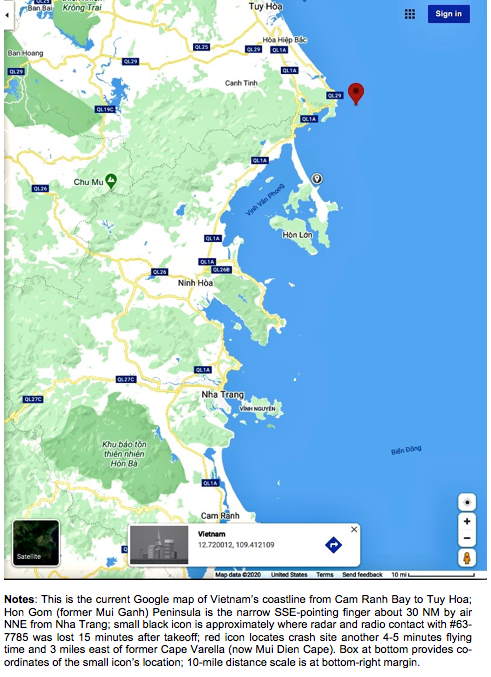

A Military Airlift Command (MAC) C-130E Hercules tail number #63-7785 based at Moffett Field Naval Air Station CA crashed about three nautical miles (3 NM) offshore Cape Varella, South Vietnam (SVN) on 17 June 1966. (Today, the former Cape Varella is the Dai Lanh Cape, also known as Cape Mui Dien). It had taken off on a routine cargo run from Cam Ranh Bay AB on the central coast of SVN at 2:20 am local time, having arrived from Kadena AB Okinawa with a cargo load about two hours earlier. It was about twenty minutes into its expected five-hour return flight to Kadena, and about 60 NM NNE of Cam Ranh Bay AB, when it exploded and crashed into the South China Sea.

Two Navy vessels witnessed the explosion, and the nearer one arrived on scene of the wreckage within minutes. They had

seen an initial explosion followed by a second explosion as the aircraft went into the water. PCF-46 was joined at the crash site by PCF-54 and

USS FORTIFY (MSO-446), which had also witnessed the crash from 23 NM away. They searched until the recovery and salvage effort was called off

due to enemy fire in the area.

There were no survivors among the eight Navy crew members and six USAF passengers. One AF passenger body and partial remains of three Navy crew members were recovered and identified four days later by the Air Force's Mortuary unit at Tan Son Nhut AB, Saigon.

MAC was a joint Air Force/Navy command. The flight crew was from the Naval Air Transport Wing-Pacific's (NATWP's) Squadron VR-7. The 22nd AF, which owned the aircraft, immediately appointed an aircraft accident investigation board (AIB) led by a colonel from its operations section. The AIB team arrived at Nha Trang AB, SVN, the closest access point to the crash site and Navy ships' crews, two days after the crash, and their work in Vietnam continued for six weeks. The board's report (AIBR), completed in September, concluded that the most probable cause of the crash was "enemy action", either hostile ground fire or sabotage; the report was non-conclusive as between the two. The Director of Aerospace Safety, HQ USAF, then based at Norton AFB CA, independently agreed that the aircraft was a "combat loss", as opposed to an ordinary accidental mishap, and therefore not chargeable to the 22 AF's flying accident rate.

The Viet Cong (VC) controlled most of the coastal area between Nha Trang and Tuy Hoa (just north of Cape Varella), including the landscape

under the final 15 minutes of the aircraft's flight path. The flexibility of the VC in moving men and equipment from one place to another was

well known. During the Navy's salvage operation in July, the area adjacent to the derelict lighthouse at Cape Varella was cleared by bombing,

offshore bombardment, and assault landings. Three days later, the salvage vessels were fired upon. VC ground fire was always present over any

area not occupied by friendly forces. Weapons of 30 caliber, 50 caliber, 37 mm, and mortars had repeatedly been used by the

Viet Cong in this area.

As a result of disrupted communication lines on the night of the incident, IFR (instrument flying rules) clearance from Saigon air traffic control had not been received before takeoff for the aircraft to ascend to its planned cruising altitude in international airspace. Fifteen minutes after takeoff, air control had lost voice and radar contact with it shortly after it had crossed the Mui Ganh (now, Hon Gom) Peninsula. The standard climb profile according to the flight plan would have resulted in an altitude of 16,000 feet by that point. Though the aircraft commander had indicated his intent to climb on the flight plan's course, because of the delay in receiving his required IFR clearance, it is possible that he leveled at 5,000 feet prior to entering controlled airspace; to have done so would have been a serious violation and posed a danger of collision with other aircraft. Saigon transmitted the IFR clearance two minutes after loss of contact, but there was no response. 4-5 minutes after loss of contact, PCF-46 and USS FORTIFY (MSO-446) first observed the aircraft above Cape Varella with its wing on fire, only seconds before it exploded. They estimated it was flying at 1,000-4,500 feet of altitude, and it appeared to have reversed course and to be on a southwesterly heading. Flak bursts at 10,000 feet from large caliber VC anti-aircraft weaponry known to be in the Mui Ganh area had been reported by other aircraft. Enemy fire could have incapacitated the cockpit crew, damaged the wings and fuel tanks, and resulted in fire and loss of control of the aircraft during the final 4-5 minutes leading up to the observed explosion and crash.

In 1999, a FORTIFY veteran posted the following on a VR-7 internet bulletin board: "I was part of the recovery crew that retrieved materials and Identification at the scene of the crash near our boat USS Fortify (MSO-446). This occurred in June of 1966. I picked up LTJG Clement Olin Stevenson Jr's laminated Navy ID card [confirmed].

A .50 caliber round had penetrated the airplane hull. I felt the plane was shot down. We spent many hours that night doing retrieval." [Henry Stevenson, Vidor, TX] While the AIBR states that the team interviewed witnesses from the Swift boats, it is not clear to what extent (if any) they were made aware of Henry Stevenson's information; in any case, the AIBR makes no mention of any evidence of .50 caliber bullet holes in the inspected wreckage. In the days following the crash, it was reported in the press that in January 1966, a C-130E piloted by LCDR Cobbs had been hit by hostile ground fire following takeoff.

On the other hand, an explosion from sabotage could occur at any altitude and could have brought the aircraft down. The VC used explosive devices extensively in sabotage efforts and had succeeded in smuggling them onto Cam Ranh and other US bases and aircraft, usually hidden in the cargo. Besides the six AF passengers, the flight was carrying cargo consisting of palletized wooden boxes that had been received from outlying SVN airfields and assembled onto pallets at Cam Ranh Bay AB by Vietnamese contracted personnel; a mechanically-triggered device (such as a hand-grenade) could have been hidden among the boxes. Chris Hobson reported in his volume "Vietnam Air Losses" (2001) that "Although very little of the aircraft was ever found, it was strongly suspected that the aircraft had been a victim of sabotage by Vietnamese communist sympathizers who worked at the base."

Among the AIBR's key operational recommendations that had been implemented during the investigation were (1) that where possible, aircraft be routed over water to the nearest point of entry upon arriving and departing Southeast Asia bases; and (2) that crews be constantly reminded of the need for close surveillance of loads and maximum security of the aircraft. A review of all U.S. C-130 losses during the Vietnam War suggests that these measures succeeded in helping to prevent any other combat losses of similar coastal airbase departing/arriving flights.

In the immediate aftermath of the crash, there was confusion over the recovery of remains and uncertainty about what had caused the accident: was it an 'accidental mishap' or a 'combat' loss from enemy action? Initially, the family of LTJG Clement O. Stevenson, Jr was notified by their son's Squadron commander that it was an aircraft accident from unknown causes, that C.O. was missing and assumed dead, and then confirmed dead and that his body had been recovered, and then later still, that no remains were recovered. The family was also told by the Navy that a VC saboteur's bomb was suspected as the cause of the crash, but that an investigation was underway and that its summary findings would be communicated when available. The AIBR concluded three months later that the aircraft loss was indeed combat-related, but that report was closely held by the Air Force and Navy until located and released (with redactions) in response to a follow-up FOIA request in 2019. No findings from the investigation were ever conveyed to the families, and AF command history records received from the AF Historical Research Agency in 2014 provide no elaboration of the

combat-loss finding.

In addition, both the Air Force records of aircraft losses and the personnel file details to this day (17 June 2020, 54 years after the crash)

list the cause of these individuals' deaths as "Non-combat, Accident", or "Non-Battle" and/or "Non Hostile, Died While Missing", even though the

Air Force determined, based upon the AIBR's findings, that all who died were eligible to be awarded the Purple Heart. The awards were made

posthumously by the AF and Navy in early 1967.

Purple Hearts are awarded only on the determination that the casualty has resulted directly from

enemy action. Yet in the document "Summary of USAF Casualties Due to Hostile Action in Southeast Asia" (USAF HQ Manpower and Personnel Center,

13 September 1984), this incident is not listed, and the HQ AFMPC did not consider that their six AF casualties resulted from enemy action.

The family of LTJG Stevenson was never informed that his partial remains had been recovered, identified by his rare blood type, and sent to the US Naval Hospital, Oakland CA on 15 February 1967. They were held one year and destroyed. As far as can be determined, the Collette and Freng families were never notified either.

The 14 men who died in the combat loss of C-130E Hercules tail number #63-7785, from Moffett Field Naval Air Station were:

It is likely there are fourteen families that have never been told of the accident investigation's findings about the circumstances of their loved ones' deaths as a result of enemy action. They may have had an inkling when in March 1967 the airmen were each awarded a posthumous Purple Heart for their wounds, even though their official records attribute their deaths to an accidental aircraft mishap.

The loss of MAC C-130E #63-7785 was NATWP's only one during the four years from the time it first began flying them in 1963 up until its disestablishment in early 1967. The Wing had been honored a month before the crash for its spotless safety record despite an intensive build-up of operations required by the demand for men and materials in Viet Nam. By mid-1966, the Wing was flying almost double the number of hours it had in the previous year, although its personnel had been increased by less than a third.

LCDR Cobbs was on his final VR-7 operational mission before retiring after 22 years of Navy service with 13,000 flying hours; he had seen service

during WW2, Korea and Viet Nam. LTJG Stevenson, LTJG Siegwarth and AN Savoy were on their first operational mission into Southeast Asia. AF

Capt Gravitte and !stLt McCall were both jet fighter pilots; they and the other four AF passengers were homebound after completing their

12-month tours of duty with the 12th Tactical Fighter Wing based at Cam Ranh Bay AB.

Return to Groups and Battles Index Page

|